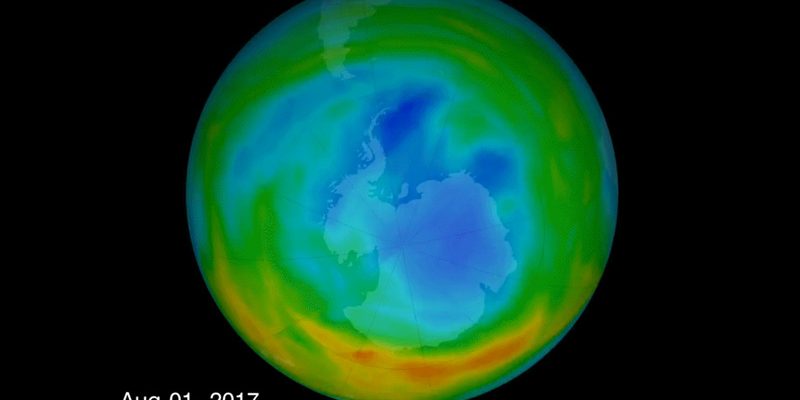

Caption: Data from NASA shows a decrease in the seasonal ozone hole above Antarctica over the last decade thanks to the phase-out of CFCs and other ozone-depleting chemicals as called for under 1987’s landmark Montreal Protocol. Credit: Katy Mersmann/NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Global warming is certainly a hot subject in the news right now, what with all the oppressive weather we’ve been having, but it doesn’t mean we’ve solved the myriad other environmental problems facing us.

That said, ozone depletion, while still problematic at certain times of year (especially in extreme southern latitudes like Antarctica) is a shining example of how we could be working together to make things better.

Researchers first noticed four decades ago that the ozone layer in the stratosphere above the clouds was starting to shrink. A 1974 research paper by Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina from the University of California at Irvine detailed how a class of synthetic chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—then widely used in refrigerators, air conditioners and aerosol spray cans—were working their way up to the stratosphere where the sun’s rays would break them down into their constituent parts. One of these parts, chlorine, reacts with the sun’s rays and breaks down ozone molecules, thinning the ozone layer that all life on the planet has evolved to depend upon for protection against harmful ultraviolet-B (UV-B) rays.

Less stratospheric ozone means more UV-B rays from the sun get through to the Earth’s surface, causing skin cancer and cataracts in humans and myriad problems for wildlife as well. Extra UV-B also inhibits the growth of phytoplankton, the lowest rung of the marine food chain. Researchers fear this culling of phytoplankton could reverberate with negative population impacts up the food chain.

Recognizing that outlawing CFCs could solve the problem, the nations of the world came together in 1987 in Montreal and agreed to phase out the production of CFCs altogether. While it will likely take another half century for the extra CFCs to filter out of the atmosphere and stop causing seasonal damage to the ozone layer, at least we’re moving in the right direction. The Montreal Protocol, ratified by 197 nations, still stands out to this day as perhaps the most successful international environmental agreement the world has ever known.

So what can we learn from our efforts to solve problems like ozone depletion that we can apply to fighting global warming? The major takeaway from the ozone depletion solution is the fact that working together across partisan lines and national boundaries is key. In 1987, the governments of the world came together, played nice and got down to business crafting an international treaty with some teeth that forced an international weaning off CFCs.

Of course, we have tried addressing global warming this way, with mixed success. Like the Montreal Protocol three decades earlier, 2016’s Paris Climate Accord was a landmark agreement where virtually all of the nations of the world agreed to cutting pollution (albeit voluntarily). But the fact that national leaders can easily pull their countries out of the climate agreement—as Trump did with the U.S.—or just simply reduce their commitments (given its non-binding terms) means that only time will tell if the Paris Accord will go down in history as the turning point in the battle against global warming—or just a footnote in the longer history of our environmental demise.

CONTACTS: “Stratospheric sink for chlorofluoromethanes: chlorine atom-catalysed destruction of ozone,” nature.com/articles/249810a0; United Nation’s Ozone Secretariat, ozone.unep.org; Paris Agreement, unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

EarthTalk® is produced by Roddy Scheer & Doug Moss for the 501(c)3 nonprofit EarthTalk. To donate, visit www.earthtalk.org. Send questions to: question@earthtalk.org.